UX Research Case Study:

When UX Testing with 1 User Beats Testing with 10

When finding actual users for UX research is difficult, can we settle for proxy users? Sometimes, yes. Other times, you’ll miss the biggest insights.

“I am a statistician and I work at the Statistical Institute for my country. I am in charge of reporting our government’s macroeconomic statistics to various data platforms run by international agencies.”

It was the first thing out of the interview participant’s mouth. Quickly the mood in the observation room changed. The multitasking and bagel eating stopped, and all eyes focused on the large screen at the front of the room.

Our researcher gave him a link to click and asked: “Have you ever used this site?”

“Oh yes,” the Central American responded with a laugh. “I use this a lot … I was just here the other day.”

Now the audience was fully locked in.

“Can you show me what you did the last time you were here?” the researcher asked.

The Actual System User

It was halfway through the morning of a 1-day UX workshop at a well-known global organization. The team in the room was a mix of designers, developers, and business analysts. The workshop was the key step in a comprehensive UX evaluation of a data tool suite run by the organization.

Throughout the morning, the team was watching video recordings of 1:1 research sessions — part contextual interview, part usability test.

The study’s participants were a mix of economists, data researchers, and macroeconomic statisticians from countries around the world. The sessions we’d shown to that point had been valuable in part because study participants felt representative of the audience for these platforms. They understood the content and could pretty easily put themselves in the shoes of a user completing a common task.

Each observer in the workshop had a pile of sticky notes with their observations — notes like “users don’t notice Upload button” or “confused by 2 levels of navigation.” Everything was going well.

Then, the interview with the Central American statistician started, and things changed.

The volume of note-taking increased. So did the specificity of the notes and the quality of the observations. More than anything, what changed was the observers’ level of focus on the session.

The statistician was saying some things that, on the surface, seemed boring. “So I go here and I upload last quarter’s trade data, like this. Then I download this spreadsheet …”

But for the team in the room, it was full of suspense. Why? Because this participant — let’s call him Diego — was an actual user. And for this project, we now realized, the difference between an actual user and a proxy was huge.

Talking to an actual user like Diego was never part of our plan. He was part of a tiny audience scattered around the globe. Our client thought the only chance of finding members of this audience and getting them to participate was with the organization’s help; and for internal political reasons, they couldn’t help.

So we went with the next best option: proxies. We recruited people who regularly worked with the subject matter — macroeconomic statistics — and who performed similar tasks as part of their jobs. “If we can find 10 proxy users, I think we’ll learn plenty,” said one of the project sponsors.

And he was right. As the workshop team observed these proxies using the platforms, they uncovered a number of UX problems for first-time or infrequent system users. This was an important focus of the project.

What the team didn’t know before the workshop was that, near the end of our recruiting, we’d lucked out and stumbled across an actual user. As they watched Diego, they began to realize that the biggest opportunities to improve the systems lay with the experience of repeat users.

Many of the tasks that tripped up first-time users were a breeze for Diego. Meanwhile, some features and functions that no other participant had discovered were deep frustration points for Diego. Like this:

“We have an admin for our accounts who doesn’t work here anymore, and there’s no way to remove her. So all the system notifications go to her email address and no one sees them. This creates a lot of problems for us.”

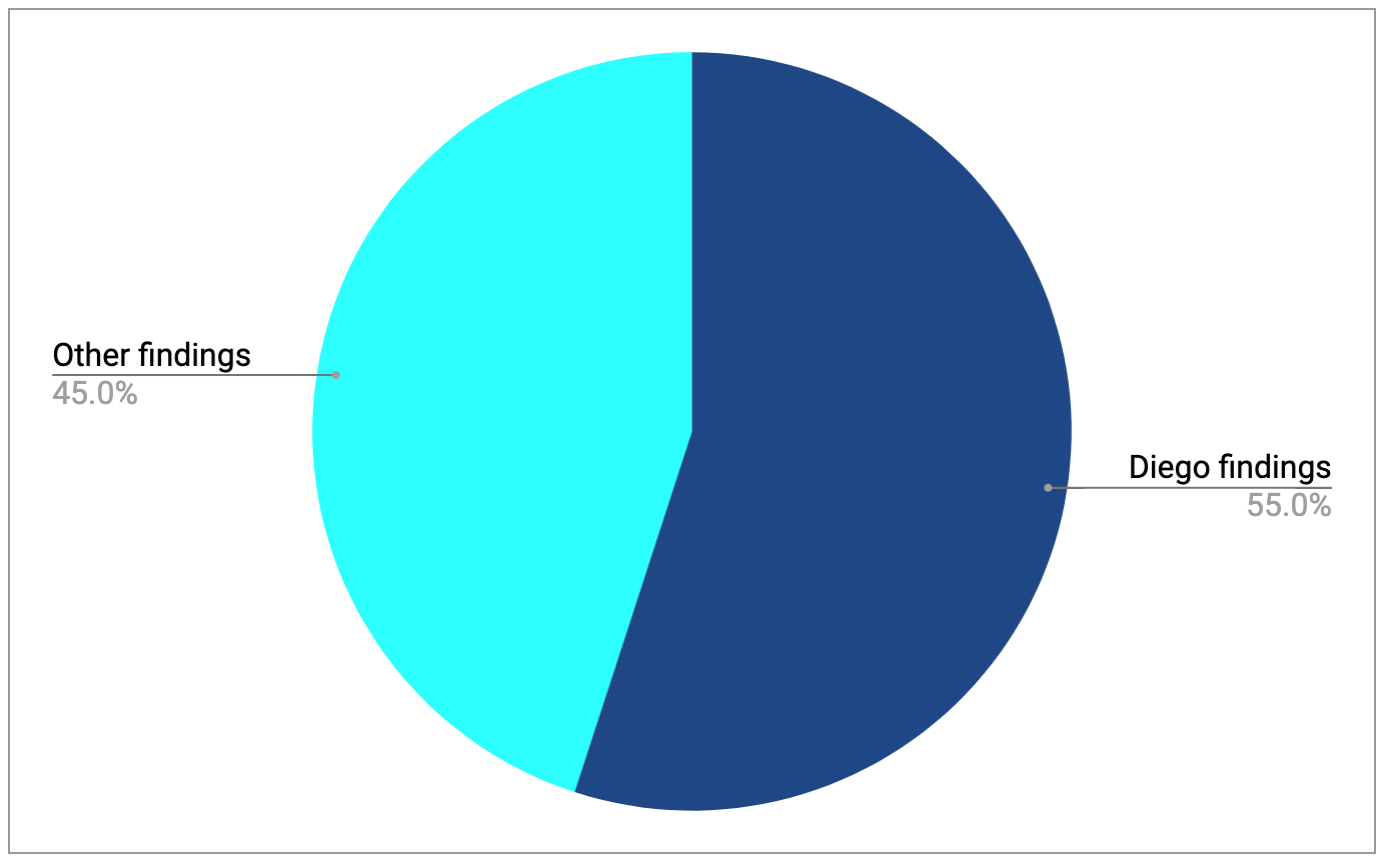

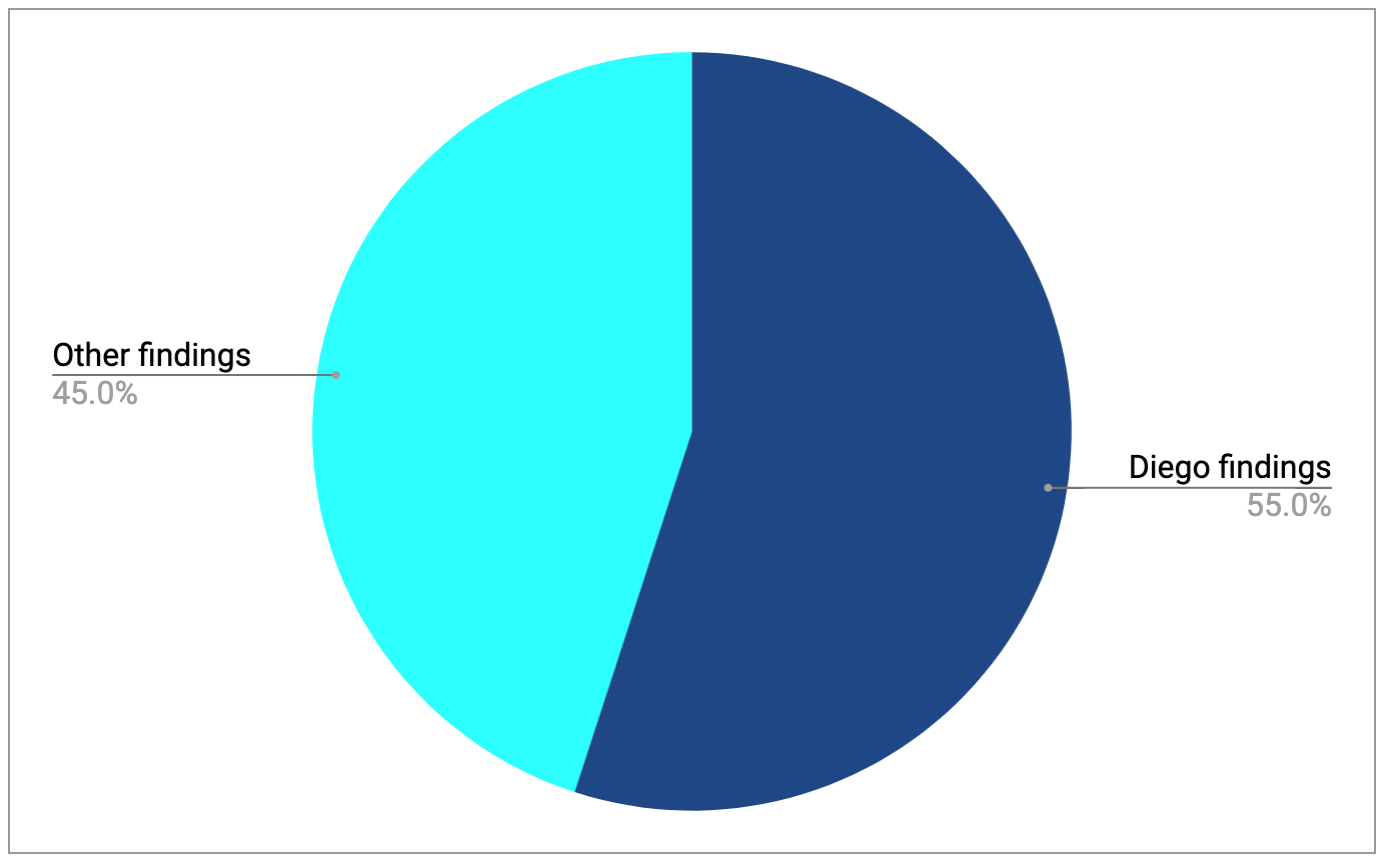

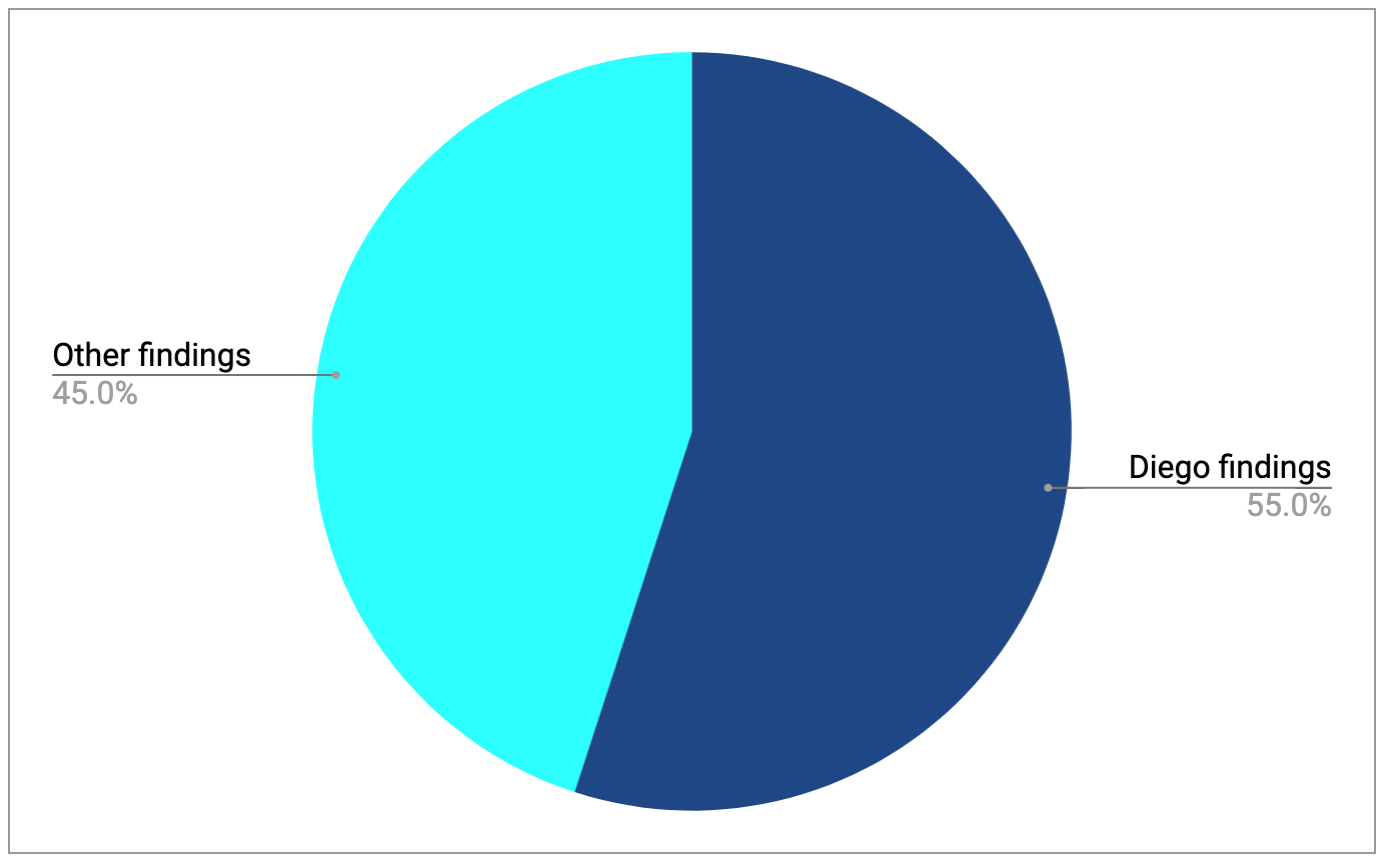

By the end of the workshop, the project team had prioritized a list of problems to tackle in the upcoming redesign. If we tied each problem to the participant session where that problem surfaced, it would look like this:

It turned out that, for this project, 1 Diego was worth 9 proxy users.

The Actual Insurance Claimant

Years ago, we were conducting usability testing of a large insurance company’s online auto claims application. We had captured sessions with 8 customers of the company, asking them to imagine they’d just been in an accident and watching as they went through the web-based form to file a claim.

We had learned plenty, certainly enough to call it a day and to help the design team come up with a list of initiatives to improve the app.

Then, near the end of the research period, the team agreed to add an Ethnio script to their customer portal. We turned on a live intercept popup for a few hours one night — with one of our researchers on standby.

The first participant we called had just arrived home from a car accident that took place an hour earlier. She was about to start filling out the online claims application when she noticed our intercept popup, and she filled out the short survey.

We called her within seconds. Once we had her on the phone, we asked her to keep doing what she had started to do. “Imagine we’re not here, just try to think aloud as you go.”

Very different audience and very different application from the data platform study. But this project too had an observer workshop, and we saw an almost identical change in the workshop energy when we replayed this session. Observers that seemed relatively engaged up to that point suddenly became super-focused.

I’ll never forget that research session and the team’s reaction as they watched and listened. At one point, the user starts shouting back and forth with her husband, trying to figure out how to answer one of the application’s questions.

Later, she hits a page with a short legal disclaimer — something about how proceeding to the next page was going to initiate a claim with the company. It was the type of language that other study participants scanned quickly and clicked “Continue” with little hesitation.

But for this user, on the heels of an actual accident and in the midst of an actual claim, the disclaimer was like a huge stop sign. She read it multiple times, struggling to fully understand the implications. “I really don’t know what to do here,” she said.

The project team had come into the project with a clear goal: to find ways to reduce the number of people who start their claim online and then call to finish. With this one real user, they suddenly had their best opportunity.

Getting Smarter About When to Settle and When to Push

The examples above are the ones where I’ve seen the biggest difference between watching actual users vs. proxy users. We’ve seen something similar when we do research on sales applications, e-commerce sites, marketing sites, and MVPs of new products: a big gap between testing with users who are in the market for something at that moment vs. users who pretend they’re in that market.

I have always liked Steve Krug’s recruiting advice in his introduction to usability testing, Rocket Surgery Made Easy:

“Try to find users who reflect your audience, but don’t get hung up about it.”

We still think that this is good advice, especially for teams starting out in user research. If finding actual users is hard and you obsess about it, you risk giving up and missing the opportunity to see how powerful any user research is.

And often, we can learn just about all we need to know from watching representative users, even if they’re not actual users. This is especially true for experiences that need to work well for first-time users and where participants can accurately act out a scenario.

Jakob Nielsen calls this the “miracle” of user testing: despite a lab-like setting, the method often generates authentic behavior and realistic findings because “people engage strongly with the tasks and suspend their disbelief.”

As we mature our research practices, however, we must increase our awareness of times when we should not settle for proxies and instead push for actual users.

This process starts by asking questions in our discovery process to help the project team decide if we should push for actual (or in-the-market) users in our study. While these questions will be unique to the product and the study, they should assess factors like:

- How niche the product’s subject matter, tasks, and personas are

- How frequently primary users are accessing the product or system

- How hard it is to find actual users

- How difficult it is for a non-user to put themselves in the shoes of an actual user

If we decide that we do need actual users for our study, we should follow some or all of these steps:

- Identify the most influential customer gatekeepers; often these are roles such as sales reps, account reps, support managers, and database owners.

- Identify the most influential project stakeholder or project friend to make the request of the customer gatekeeper (or their boss). The head of marketing will often have more success making this request than a researcher or designer.

- Equip the “requester” with an effective pitch and other materials. For instance, if we’re asking account reps for contacts, we might explain how this research could lead to product design improvements that increase customer retention.

- Be prepared for those gatekeepers to say “no” at least once, and be persistent and creative in our responses.

- When recruitment remains very hard, help our project colleagues be realistic about sample sizes. Point out that, in certain cases, a study with 2 or 3 actual users generates more value than one with 5, 10, or 20 proxies.

More Case Studies

Usability Testing with Older Adults for a New AARP Digital Platform

A team at AARP was eager to increase adoption and engagement for a new life management platform. Marketade combined usability testing and a heuristic evaluation to identify UX improvement opportunities.

Helping Mount Sinai Improve Cancer Patient Health Through Usability Testing

With a launch date looming, a team uses rapid UX testing to improve a web-based health app for oral cancer survivors and caregivers.